by Francisco Klauser

Peter Sloterdijk’s sociopolitical essay Rage and Time tells a compelling cultural history of the mediations, exploitations, and translations of rage through (and into) the great religious and political ‘cosmologies’ of Western civilisation. Rage and Time is a powerfully written book about the sociopolitical ordering, coding, and accumulation of rage; a book which, in sum, acknowledges and investigates the role of rage as one of the driving forces of human history.

Comparable with Sloterdijk’s earlier work – amongst which Critique of Cynical Reason (1987) and the 2,500-page long Sphären (‘Spheres’) trilogy (1998; 1999; 2004) are but the most acclaimed examples – Rage and Time captivates through its multifaceted and at once strident and joyful style of writing. Divided into four main sections, the book not only makes a significant contribution to our understanding of the constitutive role of affects in world politics – which is still dramatically underexplored by political theorists, despite important recent work, for example by Chantal Mouffe – but also provides a solid historical contextualisation of the most recent violent eruptions of anger, from 9/11 to the 2005 French riots.

“Of the rage of Achilles, son of Peleus, sing Goddess…”: Sloterdijk starts his ambitious world history of ‘rage and time’ with the opening line of Homer’s Iliad, the first words of the European tradition. For Sloterdijk, Homer’s epic poetry not only highlights that in Europe literally everything began with rage, but also exemplifies the antique roots of the critical question – to which the sociopolitical and religious ‘cosmologies’ are constantly responding – of how to relate collectively to the affect of rage. Sloterdijk’s reading of the Greek heroic epos, the imaginary space of gods, half-gods, and divinely chosen angry heroes, underlines that in ancient Hellenistic mythology the origins of rage and anger are neither located in the earthly world, nor attributed to individuals’ personalities. Rage is rather understood as a possessed, divine capacity, a god-favoured eruption of power. Hence the birth of the hero as a prophet, whose task is to make the message of his god-given anger an immediate reality (pp. 8-9). For Homer, to sing the praises of Achilles’ heroism also – and ultimately – means to celebrate the existence of divine forces, which are releasing society from its vegetative daze, through the mediation of the godly chosen ‘bringer of anger and revenge’.

It is from the Greek mythological relationship with rage and anger that Sloterdijk derives his own conceptualisation of rage through the figure of Thymos. Originally denominating both the Greek hero’s specific organ for the reception of god-given rage and the bodily location of his proud self, Thymos later with Plato, and following the general transformation of the Greek psyche from heroic – belligerent to more civic virtues, stands for the righteous anger of the Greek citizen as a means of defence from insults and unreasonable attacks (pp. 22-25).With the figure of Thymos set against the psycho- analytical focus on Eros, anger, for Sloterdijk, is not only a vent for frustrated desires, but also, and rather, a reactive manifestation of offended pride. Yet, and in the tradition of both Sloterdijk’s earlier (1985) novel on the birth of psychoanalysis and of his critical study of psychoanalysis in the first volume of Spheres (1998, p. 297), Sloterdijk does not per se negate the merits of psychoanalysis for an understanding of the affective realm of human existence. Rather, Sloterdijk’s critique focuses on the limitations of the libido-centrist psychoanalytical vocabulary and thinking.

In conformity with its basic erotodynamic approach, psychoanalysis brought much hatred to light, the other side of live. Psychoanalysis managed to show that hating means to be bound by similar laws as loving. Both hating and loving are projections that are subject to repetitive compulsion. Psychoanalysis remained for the most part silent when it came to that form of rage that springs from the striving for success, prestige, self-respect, and their backlashes. (p. 14)

From this standpoint, a theory of rage, for Sloterdijk, is primarily a theory of the politico-religious mediations of the processes of overcoming offended pride and of longing for revenge.

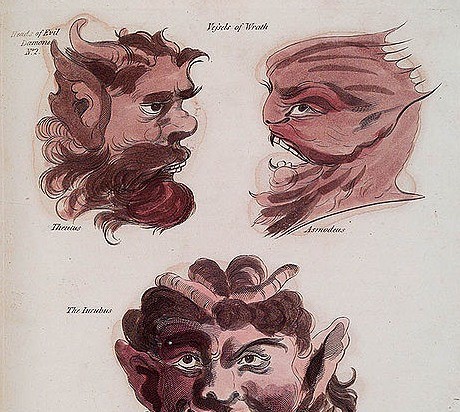

As we move from the ancient Hellenistic to the monotheistic Judaic world, the politico-religious coding of rage is fundamentally altered, as Sloterdijk shows in the second section of his analysis. In the Jewish faith, the angry hero becomes the metaphysical, wrathful God. Rage is thus conceived as the exclusive privilege of God, the very condition of his absolute sovereignty and power, which is directed in punitive form against his own people or against his chosen people’s enemies. As Sloterdijk subsequently shows, this cosmology of wrath of the Old Testament undergoes another set of structural changes in the medieval rage-conception of Catholic teaching, based on the double process of the earthly demonisation and of the metaphysical suspension of rage.

Had Europeans not heard about pride – or likewise rage – from the days of the church fathers, when such impulses would have been taken as signs pointing to the abyss for those cast away? (p. 17)

Based on the Christian axiomatic association of rage and eternity, God thus becomes the location of a transcendent repository of suspended human rage-savings and frozen plans of revenge.

What is important to note in this context of the Christian depictions of the Inferno is that the increasing institutionalization of hell during the long millennium between Augustine and Michelangelo allowed the theme of the transcendent archive of rage to be perfected. (p. 97)

In this light, and relating to the theorisation of human affects more generally, Sloterdijk’s analysis of ‘rage and time’ points towards the need to consider the world of affects not only in its fleeting and intimate, but also in its relational, resource-like, dimension, as the object of specific rage-administrating projects. Hence the possible reading of Rage and Time as a theory of the accumulation of affect.

This problematisation of anger and resentment as the objects of politico-religious accumulation and regulation is further developed in the third section of Rage and Time, relating to another ‘thymiotic’ revolution in Occidental civilisation with the emergence of the communist ‘World Bank of Rage’. Unlike the Christian referential of a metaphysical archive of rage, Sloterdijk shows that the communist ‘rage economy’ offers an earthly rooted programme for the canalisation and sociopolitical actualisation of individual rage-investments. The communist code of rage thus implies another project for the suspension and delegation of anger (to the earthly instance of the professional revolutionary) as a means to concentrate and maximise the power of individually deposed rage-investments, linked with the promise of substantial interest payments in the form of a better, newly created society. In Marx and Engel’s words, “all history is the history of making wrath productive”.

As the counterpoint to the communist doctrine of a party-led collectivisation of rage, Sloterdijk discusses the bourgeois-biased individualisation and romanticising of rage, exemplified by Alexander Dumas’s Count of Monte Cristo, as yet another exemplary ‘instruction manual’ of how to deal with rage. This individualist-capitalist approach to rage is further explored in the last section of Rage and Time, referring to the contemporary world of mass culture and consumerism, which is interpreted by Sloterdijk as a general transformation of rage-dynamic into greed-dynamic and lust-dynamic systems. Sloterdijk argues that in the aftermath of the Western rage-projects in their red, white, and brown colours, the figures of the resolute warrior and the prolific mother are substituted by the ambitious lover and the luxury consumer.

Yet, if consumerism conceals and redirects individual, pent-up rage towards new civic duties of enjoyment and desire, it also creates an explosive ‘multiegoistic situation’, which is deeply shaped by rather unarticulated and unregulated manifestations of disappointed rage communities. Pointing to the remarkable lack of political collection and administration of the thymiotic energies erupting in the 2005 French riots, the contemporary world, for Sloterdijk, is also a world of multiple decentralised movements of disoriented rage-holders. It is in a sense a postmodern world, in which no theory or project of global meaning prevails as a unitary mediator for the suspension, accumulation, management, and goal-directed increase in value of entrusted, individual rage investments. “Neither in heaven nor on Earth does anyone know what work could be done with the ‘just anger of the people’.” (p. 183) We hence rediscover one of the leitmotifs in Sloterdijk’s oeuvre, referring to the causes, modalities, and effects of the Enlightenment-induced destruction of unconditional, absolute truths in respect of both ontology and morality. For example, in Critique of Cynical Reason, Sloterdijk addresses this problematic through the notion of ‘cynicism’, as a diffuse, generalised attitude of discontent, following the loss of the great ideals and truths of older cultures. In Spheres, this theme emerges somewhat reformulated, in the opposition between the globalising spatialities of classical holistic thought and the foam-like spatialities of modernity.With Rage and Time, Sloterdijk further pursues this investigation through the discussion of the contrasting politics of anger in the past and present world.

On the last fifteen pages of Rage and Time, Sloterdijk asserts the potential of political Islam – based on its missionary dynamism, battle-centred cosmology and demographic strength – as an alternative ‘World Bank of Rage’ in the contemporary sociopolitical context. On the one hand, Sloterdijk acknowledges the actual and future power of political Islam to reunite parts of the disappointed Muslim world; on the other hand, he questions the ability of political Islam’s creative forces to develop an alternative oppositional movement of global meaning to the current capitalist mode of existence. In this, Sloterdijk stresses the current technological, economic, and scientific shortcomings of political Islam and thus its general limits in creatively shaping the socioeconomic conditions of humanity in the 21st century. Sloterdijk’s reading of political Islam thus focuses more on its high-risk potential in the form of intensified Muslim civil wars, or further amplified conflicts with Israel, than on its oppositional role within the Western world itself.

However, whilst Sloterdijk’s analysis of communist and Judeo-Christian anger-semiotics expands on a broad body of historicocultural insights, the investigation of current mediations of anger in the Middle Eastern world and in the context of post-9/11 Western politics appears to have been somewhat slighted. Readers of Rage and Time may search in vain for a more profound analysis of the differences and parallels between the historical and the contemporary sociopolitical coding of anger and revenge, which could have resulted in a more substantial prospective examination of the upcoming sociopolitical challenges in the 21st century. In this light, Sloterdijk’s open-ended conclusive consent of a general need for a morally based “education program” and a “great politics” of “balancing acts” (page 229) remains relatively vague, resembling a well-intended, yet somehow unrealistic, wish.

The main strengths of Rage and Time certainly lie in its very rich, cultural-historical approach and in its immense suggestive power for further analytical and empirical research into the complex role of rage and anger in contemporary politics – from the current semiotics of the war on terror to the Western imaginaries of modern forms of heroism, for example. Sloterdijk’s analysis strongly confirms the critical importance and high potential of such a research agenda. From this perspective, and in addition to Sloterdijk’s exclusive focus on the various forms and mediations of rage, one of the central challenges for future analyses will be to undertake detailed and comparative investigations into the ways in which political and religious semiotics and practices are combining and mediating different human affects simultaneously. This will – for example – allow a more substantial engagement with the widely developed body of empirical research on fear and hope. Rage and Time provides the perfect starting point to address these questions and to further elaborate upon the complex relationships between the political and the intimate (affective) dimensions of social existence.

Peter Sloterdijk: Rage and Time. A Psychopolitical Investigation.

Columbia University Press, New York 2010.

ISBN: 978-0-231-14522-0

Cloth, 256 pages, US$34.50.

Francisco Klauser is assistant professor in political geography at the University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland. His work focuses on the relationships between space, surveillance/risk and power; he also has research interests in urban studies and socio-spatial theory.

An earlier version of this review, based on the German edition of Zorn und Zeit, was first published in Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, Vol. 27 (No. 1/2009), a publication of Pion Ltd., who have given kind permission to reproduce part of the material in the present review of Rage and Time. Reproduction of the present version requires permission from all the copyright owners concerned. (c) 2010