by James R. Daniel

What sort of a life has new technology given us? To abide by the gospel of the digital age, it’s an ecstatic one. In recent years, a litany of tech advocates from Silicon Valley CEOs to futurists like Ray Kurtzweil have framed technological advancement, particularly in the area of digital communication, as the patron of the good life. As Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt told Berkeley graduates in 2012, “connectivity can revolutionize every aspect of society — politically, socially, economically.”

A similar question, albeit with a profoundly different answer, has oriented the prolific career of Korean-German philosopher Byung-Chul Han. In over twenty books, Han, a professor at Universität der Künste Berlin, has considered how capitalist accelerations and digital technology have undermined global society. In his most renowned work, The Burnout Society [Müdigkeitsgesellschaft] (2015, first published in German in 2010), Han details the existential fatigue resulting from the rise of the entrepreneurial self. Contemporary society, he claims, exhausts us, having stripped away all accoutrements save the drive to succeed. In The Transparency Society [Transparenzgesellschaft] (2015 [2012]), he argues that the vanishing privacy of the digital age, touted by the tech scene as a boon for social cohesion, furthers neoliberalism’s project of surveillance and control. These critiques, while they may track familiar lines in their analysis of the faulty logics at the heart of our technologically dependent culture—Bernard Stiegler and Maurizio Lazzarato are similarly inclined—offer one of the most cutting responses to Silicon Valley’s cyber-utopianism and the cult of neoliberal self-actualization.

In two recently translated books, In the Swarm: Digital Prospects [Im Schwarm: Ansichten des Digitalen] (2017 [2013])and The Agony of Eros [Agonie des Eros] (2017 [2012]), Han turns his eye to the digital terrain of contemporary social relations. The former surveys the crisis of the commons and the technologically mediated loss of political subjectivity, theorizing the swarm as the key social actor on the global stage. The latter takes up technology’s devastation of the romantic relationship, suggesting that our reliance on the digital inhibits true intimacy. While entirely distinct works, both share a critique of digital capitalism’s betrayal of the human subject and theorize how a loss of the negative (in thought and in human relations) undermines contemporary life. Accordingly, against the increasingly common assertion that digital innovation offers us a way out of the isolation, poverty, and subjugation that defines late capitalism, Han maintains that technology has only buried us deeper.

In the Swarm is chiefly concerned with the question of collective subjectivity in the age of digital communication. In Han’s view, the Internet’s isolation of individuals has led to the emergence of a political unit without intersubjectivity or the capacity for substantive political engagement. More mob than assemblage, the swarm is a body that “lacks the soul or spirit of the masses” (10), a collective that subsumes rather than expresses individuality. Wielding a single weapon, the “shitstorm” (3), swarms unleash digital waves of destruction obliterating norms of governance and discourse across the Internet. Lacking the discipline of organized political collectives, Han regards swarms as ultimately ineffectual, haphazardly attacking individual victims rather than organizing against worthier sites of neoliberal authority (12).

This disparaging view of the potential for contemporary political organizing crucially positions itself against post-Marxist theorists far more sanguine about agency in the context of late capitalism. Han explicitly contrasts his model of the swarm with Michael Hardt, Antonio Negri, and Paolo Virno’s concept of the multitude, “an aggregate of singularities communicating with each other over networks and acting collectively” (12). For Han, this mode of collective deterritorialization responds to an outdated Marxist model of class society based upon the proletariat’s subjugation by the ruling class (13). On Han’s account, the contemporary subject is self-subjugating, an isolated and disconnected figure unable to find collectivity with other similarly disconnected subjects (13). Such a position underscores the singularity of Han’s critique as it negates the cautious optimism of leading critical theorists on dissent—Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s rhizome is implied here as are theorizations of dissent by Alain Badiou and Slavoj Žižek. Against the prevailing tendency among critical theorists to locate the potential for new forms of political agency to emerge from networked relations, Han understands the network itself as maintaining political quietism.

Han’s other interlocutor in the text is Czech-born philosopher Vilém Flusser, a critic whose technological idealism parallels that of Silicon Valley. Throughout the book, Han consistently positions himself against Flusser’s techno-utopian position, locating peril where Flusser sees only possibility. Han opposes Flusser’s praise of the atrophy of the human body in the digital era, a condition that Flusser welcomes as the human being merges with technology and enters an age of leisure (32). For Han, atrophy represents the loss of the potential of resistance and the hegemony of labor: “the utopia of play leads to a dystopia of achievement and exploitation” (33). Against Flusser’s call for a new anthropology based on the digital world’s capacitation of invention and the merging of art and science, Han sees the establishment of solipsism and social isolation, calling digital networking “a narcissistic ego machine” (48). Regarding Flusser’s prediction of technology’s role in establishing a more democratic politics, Han portends the decline of discourse and the substitution of consumerism for politics: “Consumers buy what they wish, following personal inclination. Like is their motto. They are not citizens” (69).

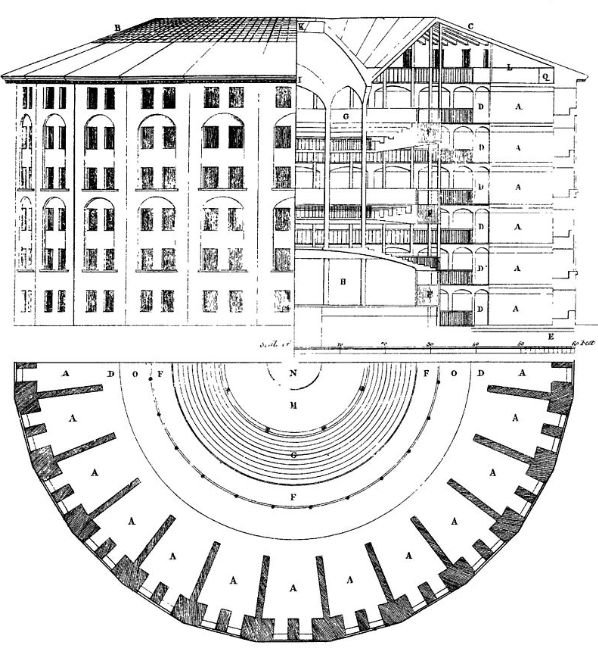

Cumulatively, the work can be understood as a renovation of Michael Foucault’s critique of biopolitics, neoliberalism, and disciplinary society. While Foucault’s project concludes with the emergence of these forces, Han follows them into their flourishing. Against the explicit disciplinary of Bentham’s Panopticon, with its imposed isolation, Han regards the Internet as offering the false promise of liberation. As he argues, consumerism, social media, and smart devices have sold discipline in the guise of agency and affluence. “Digital technology” he writes, “has perfected Bentham’s Panopticon” (75). Further extending Foucault’s critique, Han asserts that power is now exerted not through biopolitics but “psychopolitics” (78), power that intervenes in “psychological processes themselves” (78). For Han, psychopolitics have closed the circle instantiated with the birth of the biopolitical, governing our “unconscious logic” (80) and entirely mediating our approach to reality as well as our embodied practices.

The Agony of Eros, whose introduction is penned by Alain Badiou, investigates the narcissism of romantic relationships in the digital era. For Han, lost is our capacity to see the Other as Other. Instead, the false freedom of the entrepreneurial self immerses the contemporary subject in the capitalist drives of “debt and default” (11), transforming the negativity of sex to the positivity of achievement. As Han writes, “When otherness is stripped from the Other, one cannot love—one can only consume” (12). On his account, such a substitution represents an inherent betrayal of the loving relation by the engine of capitalism as “Otherness admits no bookkeeping” (16).

A crucial outcome of this loss of otherness, for Han, is the attendant rise of “bare life” (21), what Giorgio Agamben has theorized as life exposed to political violence. In Han’s assessment, as we flee from negativity in all its various forms (sex and death), we indulge a cultish devotion to both health and work (19). Hence, we instantiate our physical existence and deny the potentiating encounter with otherness that eros provides (20). Contemporary global society, with its “Work Hard, Play Hard” lifestyle typified by increasingly long workweeks and cult-like group exercise culture precisely exemplifies such resistance to otherness. As Han argues, this denial perpetuates an attenuated half-life in which we subsist, “too dead to live, and too alive to die” (26).

As in Han’s other critiques, the text constructs the digital as accessory to the eradication of otherness in contemporary culture. On his account, pornography, and its digital proliferation, profanes eros by submitting it to a calculus of positivity (29). Pornography, in other words, by revealing what is meant to be done behind closed doors, removes all mystery from the sexual act by displaying it in lurid detail. Following Agamben’s analysis of profanation, Han argues that as concealment and occlusion are crucial for the erotic encounter, the revelatory nature of pornography as exhibition precludes eroticism (32). “Capitalism,” he further notes, “is aggravating the pornographication of society by making everything a commodity and putting it on display” (32). Han likewise credits the tendency of the digital world to display with annihilating our capacity to draw upon our interior resources of imagination and fantasy. As he argues, “faced with the sheer volume of hypervisible images, we can no longer shut our eyes” (40). For Han, digital culture’s capacity to realize and display the fantastic obviates the need for invention and accordingly turns the productive work of the imagination into the passive work of consumption.

Like in his critique of In the Swarm, The Agony of Eros similarly credits capitalism, the digital, and the reign of positivity with political impuissance. In Han’s assessment, the substitution of the purely sexual desire (epithumia) for passion (thumos) precludes mass political subjectivity (44). Just as digital connectivity paradoxically precludes the establishment of meaningful political collectives, Han similarly suggests that the pornographic impedes intimacy. Insofar as the intensities of neoliberalism and the digital draw us away from others and into ourselves, the exchange of the pornographic for eros, Han claims, robs us of our capacity for political resistance (45). Even more disastrously, Han suggests that esteeming the visible for the unseen ultimately privileges quantifiable, data-driven thinking at the expense of philosophical inquiry. As philosophy engages in inquiry of occluded depths, it is, at heart, an engagement with and a desire otherness. As Han writes, “Eros infuses thinking with a desire for the atopic Other” (53).

While both texts are exquisitely theorized, the determinative role Han ascribes to negativity may strike some as reductive. For Han, it is the loss of the negative that is ultimately at the heart of the crisis of eros and our digitally mediated isolation. Badiou notably questions this assessment of negativity in his introduction to The Agony of Eros, writing, “Must absolute negativity be mustered to counter the crass positivity of repetitive, self-serving gratification?” (xi). To extend Badiou’s question, why is a return to a negative dialectic (and it would certainly be a return) a means out of our contemporary bind? Putting aside the question of whether such a return would be possible, how would a rediscovery of the negative not ultimately be regressive?

Han is certainly careful to avoid any trace of nostalgia in his condemnation of positivity, yet by locating the contemporary crisis in an imbalance of positivity wrought by the digital, his analysis seems to tempt it. Here, Han encounters the thorniest problematic of digital criticism, namely the question of how to condemn digital supremacy without implicitly appealing to technophobia. In part, Han’s response lies in the structure of his critique of negativity. As Han critiques the overabundance of the positive without offering a solution or political program, he presents a negative, non-affirmationist response to the crisis of positivity. Because an explicit tactical response or a political program would indulge a pornographic tendency to display what is to be occluded, internal, and cognitive, Han demurs. Such silence following his critique, accordingly, should not necessarily be viewed as indecision but rather as an invitation for the reader to engage the negative on their own. However, Han’s silence additionally emphasizes the supremacy of the digital and the inherent difficulty of theorizing other possibilities. Effectively, Han’s silence also intimates that digital capitalism is hegemonic precisely because it brokers no alternative.

Byung-Chul Han,

In the Swarm: Digital Prospects

Translated by Erik Butler

Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2017

ISBN: 9780262533362

104 pages, Paperback, US$ 13.95

Byung-Chul Han,

The Agony of Eros

Translated by Erik Butler

Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2017

ISBN: 9780262339230

88 pages, Paperback, US$ 12.95

James Rushing Daniel is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor of writing at Philadelphia University.