by Thorsten Botz-Bornstein

Serious essays on films are normally of an academic nature. Thus, it is no surprise that a philosophical film like Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979) has attracted the attention of several academic philosophers. My first thought when I heard of Dyer’s project was: how can a writer (not a philosopher or academic) write a whole book about a film? My next thought was: why Stalker and not Nostalghia? To be clear right at the beginning, I am one of those academic philosophers.

Dyer leaves no doubt that for him, Nostalghia is a sort of self-celebratory, pretentious kitsch movie that he has despised from his early youth on while Stalker was a revelation. Watching it for the first time in a godforsaken cinema in Gloucestershire in the 1980s, he realized that the film was bound to determine his entire future existence. Well, that is what Nostalghia was for me. Is that how some people become writers and others philosophers?

The answer is no. What matters is the difference between Gloucestershire and Westphalia. I am serious. Reading the book, I not only came to understand Dyer’s point about the difference between Stalker and Nostalghia, but – without doubt due to my keen philosophical spirit – I now understand it even better than Dyer understands it himself: Stalker is zen while Nostalghia is not. Stalker is Bach while Nostalghia is a Mozart opera. Stalker is a viola da gamba sonata while Nostalghia is similar to Händel’s mindless pom-pom, pom-pom bass.

Where do I get all this from? From another Brit, R.H. Blyth, who did with Zen Buddhism more or less what Dyer is doing with Stalker: expanding it. In his Twenty-Five Zen Essays from 1962 (originally the fifth volume of his Zen and Zen Classics), Blyth divides the whole world into manifestations of either zen or non-zen (with intermediate states between them) and spells out what many of his readers have found most plausible ever since: Händel is ‘more zen’ than the self-pitying Schubert, who is ‘more zen’ than bombastic Italian operas, and with Chopin and Wagner (!), things are getting as ‘un-zen’ as anything on this planet. Almost.

What is the contrary of zen? The moral, the beautiful, the intellectual, the emotional, the world-weary, the philosophical. Blyth’s final conclusion is even crueler than that: The Brits are the most zen-like culture in the entire Western hemisphere and perhaps even beyond. In any case, they are much, much, much higher up on the zen scale than the hopelessly Heidegger-heavy Germans who are culturally insensitive to the noble austerity of the zen spirit (even Händel was merely a “jolly good fellow”). Anyone who has ever sat for more than two hours on the antique wooden benches of Oxford’s dining halls understands what Blyth is talking about.

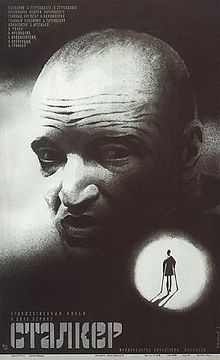

A man named Stalker guides a writer and a scientist through “the Zone”: an apocalyptic wilderness supposedly endowed with supernatural qualities. Rumour has it that a meteorite crashed into the zone twenty years before, creating a kind of cosmic abyss. Inside the Zone there is a Room said to grant people’s most intimate wishes. Porcupine, Stalker’s teacher, had entered the Room and, a week later, became immensely rich. The conflict between his mental inner reality and the reality outside had been so big that he committed suicide. In the end, none of the men dare enter the Room.

I do not know if Dyer knows Blyth, but he mentions Allan Watts, who is a similar ‘expander’. However, Dyer’s book is zen, just like the film he is writing about. Dyer talks about the serious in a lighthearted fashion and becomes profound by doing so. Is this not – in a formula – the contrary of what philosophy is doing most of the time? (And much of philosophy is German.)

Dyer himself says that the book is not a synopsis but an amplification of the film. Amplification towards what? Towards the metaphysical, of course. The book is philosophical in that it asks essential questions: what is film, what is literature, what am I, the writer? Nevertheless, Dyer’s approach is peculiar. He is not writing philosophy, he is not analyzing, and he is not even telling us the story of the film. “Literary anthropology” comes to mind, which does indeed exist. I know some self-critical and repentant philosophers (not all of them Germans) who have consciously turned towards that genre. Dyer himself mentions “Tarkovsky’s filmic archeology of the discarded” (p. 117) and I believe that this is exactly what Dyer is doing himself. The ruminating exploration of places draws us into Stalker, which is a film about a place (the Zone). Dyer retells this place with all its décor, colors, flickering lights, noises and smells. We might have seen the stone in the water, but Dyer lifts it up and tells us what is underneath. Finally, his anthropology of things brings us closer to the metaphysical meaning of the film (he does not identify the 1961 Peugeot 404 convertible, though).

Having started talking about zen, I want to go on a little (I am imitating Dyer’s style). In my opinion, Stalker puts forward zen as the religion of the age of post-secularism and Dyer is showing exactly that. I am not saying “neo-religious age” but “post-secularism”, and to make it clearer, I should perhaps call it “secular post-secularism” to further distinguish it from “religious post-secularism.” The differences are complicated and cannot be explained here. The former option can be found in the existentialist religion of Nietzsche and Dostoyevsky whereas the latter is rather that of the Southern Baptists and the Muslim Brothers of Cairo. Stalker’s Writer is a secular post-secularist who “has gone from extreme skepticism to fearful belief” (p. 137) – but who will return to skepticism sooner or later. At some point, Writer clutches a weapon but is ready to let it drop when Stalker tells him to. That is exactly what makes the film so zen and so deliciously (and secularly) post-secular. Writer would be ready to believe in the Zone, but at the same time, nothing of what he experiences can convince him of its superior character.

Some things do not work: “Writer is the one doing the drinking—maybe he should have been called Drinker.” Dyer’s countless rantings about the vulgar films of Lars von Trier and about the “witless Coen brothers” on the other hand, are interesting and always to the point.

Dyer expresses his post-secular feelings about the film like this: “The Zone is not simply a source of solace, the heart of Marx’s heartless world, it is a source of torment, a system of traps that constantly teases and threatens not just his clients but Stalker himself. No one is immune to the capriciousness of the Zone” (p. 90). The entire film works with the intensity of his despair and – strangely – also with the intensity of hope. Dyer attempts to grasp the post-secularist constellation of despair/hope by researching Stalker and by intermingling the film with his own existential situation. Saying that “the film is in some way about itself, a reflection of the journey it describes” (p. 123), Dyer manages to capture Stalker’s self-reflexive tone and produces a Stalker of its own. What is film, what is literature, what am I the writer? Can anybody “see their – what was considered to be the – greatest film after the age of thirty?” What does it mean to see a film at a young age, to see it again as a disinterested adult? Is it like trying to come to a definitive assessment of your own childhood?

There is a nice allusion to Rilke and his idea that all Russians are sort of proto-Germans in their profoundness and unconditional (crazy?) search for truth. Are Russians zen? Too late to ask Blyth.

And finally: What is a book? What is a book for Dyer, the writer? He tells us what he feels when he receives a copy of his new book: “The next moment comes not when the book is finished … but some time after it is published, when you see it for what it is… Then you see that actually those big desires and hopes, your deepest wishes, turned out not to be so deep at all…” (p. 186). Ha, I found what I was looking for: a point clearly demonstrating that philosophy is superior to literature because a philosophy book can be so entirely incomprehensible that its incomprehensibility alone gives the author full satisfaction or, more precisely: gives him hope that, even in a hundred years, people will still be trying to make head and tail of what he has written. Not that he believes anybody would do this (philosophers are not naïve), but he hopes that somebody will do it. This plunges us into the central subject of Stalker with its Room in the middle of the Zone, which grants wishes but yields disappointment after disappointment, even though – paradoxically – it creates the one thing that humanity needs in a post-secular age: hope. Hope implies a sense for the future and a discontent with the present because what would we need hope for otherwise? This paradox is implicitly contained in Stalker, and Dyer is making it explicit. It is exactly the paradox that, most probably, neither Southern Baptists nor Muslim Brothers will ever figure out.

Interestingly, Dyer mentions secular, over-happy Americans who have similar problems with the paradox of hope and should perhaps be sent to the Stalker school: “When you’re happy, hope, like all the other big questions … becomes meaningless. It is possible, in parts of California particularly, to live a life full of happiness (for what is here now)” (p. 211). Did Blyth not say that the world-weary are un-zen? I don’t remember if he says anything about the overly happy.

The Zone is a matrix and a reality at the same time. Dyer reproduces a Zone in the form of a reflection about a spacein which we are confronted with our hidden wishes and daydreams. In that sense, every book is a Zone and every work of art is a Zone. That might be the gist of Stalker. There is actually, according to Blyth, also a lot of zen in Mozart (though not as much as in Bach). So what about Nostalghia? I still have hope.

Geoff Dyer: Zona. A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room

ISBN-13: 978-0857861665

Price: GBP16.99

Edinburgh, Canongate, 2012, 228pp.

Thorsten Botz-Bornstein is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at the Gulf University for Science and Technology in Kuwait. He is the author of Films and Dreams: Tarkovsky, Bergman, Sokurov, Kubrick, Wong Kar-wai (2007) and has written a number of books on topics ranging from intercultural aesthetics to the philosophy of architecture.